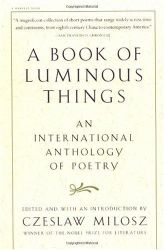

A book of luminous things: an international anthology of poetry

Czeslaw Milosz

Milosz, Czeslaw;

A book of luminous things: an international anthology of poetry

Harcourt 1996-09-30 (hardcover)

ISBN 9780151001699 / 0151001693

topics: | poetry | anthology | nobel-1980 | anthology

a superb anthology, very high on my "where-the-page-falls-open" test. almost all the poems work for me. and they are all new - from a surprisingly diverse set of cultures, mostly eastern europe and china.

Themes

The 326 poems are grouped into eleven themes - - nature - birds, flowers, insects, weather, etc.(40) - the moment (38 poems) - people among people - portraits, tense moments (36) - woman's skin - love, physicality (36) - situations (34) - places (32) - travel (32) [travel by train, by boat...] - nonattachment -a detached view, not quite mystic (30) and shorter sections on "secret of a thing" (24), "history" (16), "epiphany" (8), The arrangement works- quite often the juxtaposed poems do converse, as in the beautiful selection of poems on train travel. Any linear arrangement of texts is a problematic thing, but I feel that like all else about this book, there is clear evidence of considerable thought and passion that has gone into this, and surely this is to be welcomed by any reader...

Most popular poets in Luminous things

Czeslaw's favourite poets, at least those selected the most, appear to be: ------------------------------------------ 12 Anna Swir [Polish poet WW2 nurse, 1909-1984) (wiki) 11 Walt Whitman 11 Po Chü-I [Chinese Tang poet Bai Juyi; Henan / Xian, 772-846] (wiki, poems) 11 Tu Fu [Chinese Tang poet; Henan / Xian, 712-770] (wiki) 10 Wang Wei [Chinese Tang poet, Shanxi / Xian, 699-759] (wiki) 7 Jean Follain [French author, poet, and lawyer, 1903-1971] (wiki) 5 Wislawa Szymborska [Polish poet, 1923- ] (wiki) 5 Steve Kowit [US poet, NYC/Calif. 1938- ] (bio,poems) 5 Denise Levertov 5 Blaise Cendrars [Swiss-French novelist / poet, 1900-1961] (wiki, critique) 4 Rolf Jacobsen [Norwegian poet, 1907-1994] (wiki) 4 Robinson Jeffers [US poet 1887-1962] (wiki) 4 Kenneth Rexroth 3 Aleksander Wat [Polish poet, 1900-1967] (wiki) ---------------------------------------------- Thus the coverage is either European (20th century), or ancient Chinese (Tang dynasty). There are a couple of middle-eastern poets, none from south asia.

Error in attributing a poet

There is an error of attribution in the book. The poem "When he pressed his lips" is by an ancient Sanskrit woman poet, Vikatanitamba translated by Steve Kowit. Here, the poem appears under Kowit's name, and that it is a translation is quite lost. The text does bear the notation "after Vikatanitamba" at the bottom, but to me it seems like a vestigial eurocentric bias; how many poets would translate dante and give only a note like this? That the poem is a translation and not an inspired re-creation is clear if we compare nother translations of this work, by Octavio Paz and by Daniel Ingalls (both given below). Thus, Vikatanitamba should have been acknowledged in the list of poets, and Steve Kowit also needs to make this explicit. Hopefully this may be fixed in a later edition... --- Except for this small south asian complaint, the anthology is superb - a complete delight! Part of what makes this anthology work is also the brief introductions to each piece, where Milosz sets the tone and links it up with the otherwise disparate neighbours.

Excerpts

Adam Zagajewski (Poland, 1945-): Moths p.19

Moths watched us through the window. Seated at the table, we were skewered by their lambent gazes, harder than their shattering wings. You'll always be outside, past the pane. And we'll be here within, more and more in. Moths watched us through the window, in August. poems: poetryfoundation poets.org buffalo.edu wikipedia : Adam Zagajewski

Zbigniew Machej : Orchards in July p.29

[tr. Czeslaw Milosz and Robert Hass] Waters from cold springs and glittering minerals tirelessly wander. Patient, unceasing, they overcome granite, layers of hungry gravel, iridescent precincts of clay. If they abandon themselves to the black roots it's only to go up, as high as possible through wells hidden under the bark of fruit trees. Through the green touched with gray, of leaves, fallen petals of white flowers with rosy edges, apples heavy with sweet redness and their bitterish seeds. O, waters from cold springs and glittering minerals. You are awaited by a cirrus with a fluid sunny outline and by an abyss of blue which has been rinsed in the just wind.

Anna Swir (1909-1984)

Polish poet Anna Swirszczynska, who joined the Polish Resistance during WW2. Towards the end of the war, The resistance launched the Warsaw Uprising, a sharp push to evict the germans before the red army, thus underscoring polish sovereignty. In the event, Soviet troops actually did not enter warsaw for many months and the resistance surrendered in 63 days after nearly 200,000 polish deaths (about 3000 per day). More than 80% of Warsaw was destroyed, mostly by fire. Anna served as a nurse during this period, and the grueling scenes of this period form the basis for some of her poetry. Anna Swir has the most poems in this book. Czeslaw obviously feels she is underappreciated in English; all the poems have been translated by Czeslaw and Nathan.

The Sea And The Man (Anna Swir) p.47

(tr. Czeslaw Milosz and Leonard Nathan) You will not tame this sea either by humility or rapture. But you can laugh in its face. Laughter was invented by those who live briefly as a burst of laughter. The eternal sea will never learn to laugh.

Anna Swir : I Wash the Shirt 204

For the last time I wash the shirt of my father who died. The shirt smells of sweat. I remember that sweat from my childhood, so many years I washed his shirts and underwear, I dried them at an iron stove in the workshop, he would put them on unironed. From among all bodies in the world, animal, human, only one exuded that sweat. I breathe it in for the last time. Washing this shirt I destroy it forever. Now only paintings survive him which smell of oils.

The Greatest Love : Anna Swir 219

(tr. Czeslaw Milosz and Leonard Nathan) She is sixty. She lives the greatest love of her life. She walks arm-in-arm with her dear one, her hair streams in the wind. Her dear one says: "You have hair like pearls." Her children say: "Old fool."

Blaise Cendrars (1887-1961)

from introduction to the theme Travel: The buoyant mood of the period just preceding World War I, called in France "La Belle Epoque," is present in French poets such as Valery Larbaud and Blaise Cendrars. Larbaud invented a figure of an international traveller, a millionaire, Barnabooth, and published his presumed poems in 1908. Cendrars (in reality a Swiss, born Ferdinand Sauser) drew the images of his largely descriptive poems from both America and Russia. In 1912 he published his famous poem "Easter in New York," as important for modern poetry as is "Zone," by his friend Guillaume Apollinaire. In 1913 he wrote his long poem entitled "Prose of the Transsiberian Railway and of little Jeanne of France." His postwar poems were snapshots from different continents, often collages.

Blaise Cendrars : Fish Cove

tr. from French: Monique Chefdor, p.79 The water is so clear and so calm Deep at the bottom you can see the white bushes of coral The prismatic sway of hanging jellyfish The yellow pink lilac fish taking flight And at the foot of the wavy seaweeds the azure sea cucumbers and the urchins green and purple

Blaise Cendrars : Aleutian Islands

tr. from French: Monique Chefdor, p.79 1 High Cliffs lashed by icy polar winds In the center of lush meadows Reindeer elks musk-oxen The Arctic foxes the beavers Brooks swarming with fish A low beach has been prepared to breed fur seals On top of the cliff are collected the eider's nests Its feathers are worth a real fortune 2 Large and sturdy buildings which shelter a considerable number of traders All around a small garden where all vegetation able to withstand the severe climate has been brought together mountain ash pine tree Arctic willows bed of heather and Alpine plants 3 Bay spiked with rocky islets In groups of five or six the seals bask in the sun Or stretching out on the sand They play together howling in that kind of hoarse tone that sounds like a dog's bark Next to the Eskimos' hut is a shed where the skins are treated

Blaise Cendrars : South - I. Tampa

tr. from French: Monique Chefdor, p.81

[these poems appeared in his 1923 work, Kodak, (later retitled

Documentaires after the Eastman Co. threatened a lawsuit). Decades

later, Cendrars revealed that many of the poems were lightly edited

versions taken from the popular science-fiction novel by Gustave Le

Rouge, The Mysterious Doctor Cornelius. In his memoir -

L'Homme foudroye' (The astonished man) - said to be

close to fiction, or compulsively prone to fabrication,

Cendrars tells this version of the story:

I was cruel enough to take [Gustave] Lerouge a volume of poetry and

make him read, and confirm with his own eyes, some twenty original

poems which I had clipped out of oneof his prose works and had

published under my own name... It was an outrage...

Kodak was divided into tales from different parts of his travels in America,

"North", "Far West", "South", etc.

The train has just come to a stop

Only two travelers get off on this scorching

late summer morning

Both wear khaki suits and cork helmets

Both are followed by a black servant

who carries their luggage

Both glance in the same casual way at the houses

that are too white at the sky that is too blue

You can see the wind raise whirls of dust and the flies

buzzing around the two mules of the only cab

The cabman is asleep the mouth wide open

Blaise Cendrars : Frisco-City

tr. from French: Monique Chefdor, p.80 It is an antique carcass eaten up by rust The engine repaired twenty times does not make more than 7 to 8 knots Besides to save expenses cinders and coal waste are its only fuel Makeshift sails are hoisted whenever there is a fair wind With his ruddy face his bushy eyebrows his pimply nose Master Hopkins is a true sailor Small silver rings hang from his pierced ears The ship's cargo is exclusively coffins of Chinese who died in America and wished to be buried in their homeland Oblong boxes painted red or light blue or covered with golden characters Just the type of merchandise it is illegal to ship

Rolf Jacobsen (1907-1994) : Express Train

tr. from Norwegian: Roger Greenwald p. 92 There is no reason to stay with Chinese poetry, so I return to the twentieth century and to train travel. Very often, the train is presented as the site of observatIon by a person who travels. Beyond, out the window, there are towns, cities, and in this case a NorweBian landscape of villaBes, provokinB a philosophical reflection on the life of their inhabitants, life deprived of love, unfulfilled, with an enormous potential which waits for liberation. Express train 1256 races alongside hidden, remote villages. House after house wanders by, pale gray, shivering. Rail fences, rocks and lakes, and the closed gates. Then I have to think in the morning twilight: What would happen if someone could release the loneliness of those hearts? People live there, no one can see them, they walk across rooms, in behind the doors, the need, blank-eyed, hardened by love they cannot give and no one gets a chance to give them. What would rise higher here than the mountains-the Skarvang Hills-what flame, what force, what storms of steady 'light? Express train 1256, eight soot-black cars, turns toward new, endlessly unknown villages. Springs of light behind the panes, unseen wells of power along the mountains - these we travel past, hurry past, only four minutes late for Marnardal.

Antonio Machado (1899-1939) : Rainbow at night

A train compartment, .not necessarily what is seen movinB beyond the window, may appear as the backBround, with fellow passenBers as the object of attention, and speculation about their internal world-thouBhts, dreams. Nevertheless, the duality of motlOn internal and external seems to be important. Antonio Machado places his characters in a niBht train; the visibility of what's outside is limited. "A traveler mad with Brief" and the narrator both are busy with their reminiscences. Unexpectedly, the end is like an epiphany. for Don Ramon del Valle-Incldn The train moves through the Guadarrama one night on the way to Madrid. The moon and the fog create high up a rainbow. Oh April moon, so calm, driving up the white clouds! The mother holds her boy sleeping on her lap. The boy sleeps, and 'nevertheless sees the green fields outside, and trees lit up by sun, and the golden butterflies. The mother, her forehead dark between a day gone and a day to come, sees a fire nearly out and an oven with spiders. There's a traveler mad with grief, no doubt seeing odd things; he talks to himself, and when he looks wipes us out with his look. I remember fields under snow, and pine trees of other mountains. And you, Lord, through whom we all have eyes, and who sees souls, tell us if we all one day will see your face. tr. from Spanish: Robert Bly ---William Stafford (1914-1993) : Vacation-- p.95 One scene as I bow to pour her coffee:- Three Indians in the scouring drouth huddle at the grave scooped in the gravel, lean to the wind as our train goes by. Someone is gone. There is dust on everything in Nevada. I pour the cream.

Louis Simpson (1923-) : After Midnight p. 117

The dark streets are deserted, With only a drugstore glowing Softly, like a sleeping body; With one white, naked bulb In the back, that shines On suicides and abortions. Who lives in these dark houses? I am suddenly aware I might live here myself. The garage man returns And puts the change in my hand, Counting the singles carefully.

I Talk to My Body : Anna Swir 233

My body, you are an animal whose appropriate behovior is concentration and discipline. An effort of an athlete, of a saint, and of a yogi. Well trained, you may become for me a gate through which I will leave myself and a gate through which I will enter myself. A plumb line to the center of the earth and a cosmic ship to Jupiter. My body, you are an animal from whom ambition is right. Splendid possibilities are open to us.

I'm Afraid of Fire (Anna Swir) 296

Why am I so afraid running along this street that's on fire. After all there's no one here only the fire roaring up to the sky and that rumble wasn't a bomb but just three floors collapsing. Set free, the naked flames dance, wave their arms through the gaps of the windows, it's a sin to peep at naked flames a sin to eavesdrop on free fire's speech. I am fleeing from that speech, which resounded here on earth before the speech of man.

Po Chu-I (772-846)

Tang dynasty poet Bai Juyi (in modern Pinyin; written Po Chu-I in the earlier Giles system), has an accessible style and appears from early anthologies (unlike Du Fu). Born in Henan province, he passed his competitive exams (jinshi) at age 18 and joined the imperial service. He was prefect of Hangzhou and then Suzhou. See poems at blackcatpoems.

Po Chu-I: Madly singing in the mountains 120

[tr. Arthur Waley]

There is no one among men that has not a special failing:

And my failing consists in writing verses.

I have broken away from the thousand ties of life;

But this infirmity still remains behind.

Each time that I look at a fine landscape,

Each time that I meet a loved friend,

I raise my voice and recite a stanza of poetry

And marvel as though a God had crossed my path.

Ever since the day I was banished to Hsun-yang

Half my time I have lived among the hills.

And often, when I have finished a new poem,

Alone I climb the road to the Eastern Rock

I lean my body on the banks of white Stone;

I pull down with my hands a green cassia branch.

My mad singing startles the valleys and hills;

The apes and birds all come to peep.

Fearing to become a laughing-stock to the world,

I choose a place that is unfrequented by men.

Po Chu-i : Sleeping on horseback 172

[tr. Arthur Waley]

We had ridden long and were still far from the inn;

My eyes grew dim; for a moment I fell asleep.

Under my right arm the whip still dangled;

In my left hand the reins for an instant slackened.

Suddenly I woke and turned to question my groom.

"We have gone a hundred paces since you fell asleep."

Body and spirit for a while had changed place;

Swift and slow had turned to their contraries.

For these few steps that my horse had carried me

Had taken in my dream countless aeons of time!

True indeed is that saying of Wise Men

"A hundred years are but a moment of sleep."

Carlos Drummond de Andrade: In the Middle of the Road 8

[from Portuguese, tr. Elizabeth Bishop] In the middle of the road there was a stone there was a stone in the middle of the road there was a stone in the middle of the road there was a stone. Never should I forget this event in the life of my fatigued retinas. Never should I forget that in the middle of the road there was a stone there was a stone in the middle of the road in the middle of the road there was a stone.

Wang Wei (701-761): Song about Xi Shi 179

[tr. Tony and Willis Barnstone and Xu Haisin] Since beauty casts a spell on everyone, How could Xi Shi stay poor so long? In the morning she was washing clothes in the Yue river, In the evening she was a concubine in the palace of Wu. When she was poor, was she out of the ordinary? Now rich, she is rare. Her attendants apply her powders and rouge, others dress her in silks. The king favours her and it fans her arrogance. She can do no wrong. Of her old friends who washed silks with her, none share her carriage. In her fillage her best friend is ugly. It's hopeless to imitate Lady Xi Shi's cunning frowns. (several Wang Wei poems, including this one in a different translation, can be found at http://www.chinapage.com/poem/300poem/t300a.html)

Legend of Xi Shi

Xi Shi (c. 506BC-?) was one of the Four Beauties of ancient China. While laundering her garments in the river, the fish would be so dazzled that they forgot how to swim and gradually sunk to the bottom, while condors were so charmed that many stopped flying and plummeted to death. The idiom 沉魚落雁, (pinyin; chén yú luò yàn) "To cause fish to sink and condors to drop" is a compliment used for beautiful women. ) King Gou Jian of Yue, after being defeated by Wu, was advised by his minister Fan Li to gift Xi Shi and Zheng Dan to the Wu king Fu Chai. With these extraordinary beauties, Fu Chai forgot all about his state affairs and had his great general Wu Zixu killed. Eventually, he was defeated by Gou Jian in 473 BC. In legends, after the fall of Wu, Fan Li retired from his minister post and lived with Xi Shi on a fishing boat, roaming like fairies in the misty wilderness of Tai Ho Lake, and no one has seen them ever since. The Xi Shi Temple, at the foot of the Zhu Lou Hill in the southern part of Suzhou, on the banks of the Huansha River, commemorates her. The West Lake in Hangzhou, called Xizi Lake, (Xizi means Lady Xi), is said to be an incarnation of her.

William Carlos Williams : The Red Wheelbarrow 66

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens.

Steve Kowit : In the Morning 215

In the morning, holding her mirror, the young woman touches her tender lip with her finger & then with the tip of her tongue licks it & smiles & admires her eyes.

Steve Kowit : Notice 199

This evening, the sturdy Levi's I wore every day for over a year & which seemed to the end in perfect condition, suddenly tore. How or why I don't know, but there it was: a big rip at the crotch. A month ago my friend Nick walked off a racquetball court, showered, got into this street clothes, & halfway home collapsed & died. Take heed, you who read this, & drop to your knees now & again like the poet Christopher Smart, & kiss the earth & be joyful, & make much of your time, & be kindly to everyone, even to those who do not deserve it. For although you may not believe it will happen, you too will one day be gone, I, whose Levi's ripped at the crotch for no reason, assure you that such is the case. Pass it on.

Vikatanitamba (8th c. AD, Sanskrit) : When He Pressed His Lips 224

(tr. Steve Kowit) When he pressed his lips to my mouth the knot fell open of itself. When he pressed them to my throat the dress slipped to my feet. So much I know -- but when his lips touched my breast everything, I swear, down to his very name, became so much confused that I am still, dear friends, unable to recount (as much as I would care to) what delights were next bestowed upon me & by whom translation by Octavio Paz: Recollection At the side of the bed the knot came undone by itself, and barely held by the sash the robe slipped to my waist. My friend, it's all I know: I was in his arms and I can’t remember who was who or what we did or how (Meena Alexander, Indian love poems, 2005, p.97) see Note: attribution error above - this poem needs to be attributed to sanskrit woman poet Vikatanitamba (c. 8th c.), and this text as a translation by Steve Kowit. This poem appears as item 572 in Sanskrit Court poetry: Vidyakara's "Subhasitaratnakosa"; an anthology from the 13th c. Daniel Ingalls' has edited and translated this anthology - his translation goes: 572. As he came to bed the knot fell open of itself, the dress held only somehow to my hips by the strands of the loosened girdle. So much I know, my dear; but when within his arms, I can't remember who he was or who I was, or what we did or how. vikaTanitamba [amaru collection] p.203 Of vikaTanitamba's life, we know little beside her name, and about half a dozen poems that appear in different anthologies such as subhAsitaratnakoSha (fragrant jewel chest) the name is literally ugly buttocks, a self-deprecating style of naming that was fashionable for other women poets of the times. Her poetry is among those cited in analyses of literary style such as Anandavardhana (9th c.).

Emperor Ch'ien-wen of Liang : Getting up in Winter 226

Winter morning. Pale sunlight strikes the ceiling. She gets out of bed reluctantly. Her nightgown has a bamboo sash. SHe wipes the dew off her mirror. At this hour there is no one to see her. Why is she making up so early?

Denise Levertov : A woman meets an old lover 228

He with whom I ran hand in hand kicking the leathery leaves down Oak Hill Path thirty years ago appeared before me with anxious face, pale, almost unrecognized, hesitant, lame. He whom I cannot remember hearing laugh out loud but see in mind's eye smiling, self-approving, wept on my shoulder. He who seemed always to take and not give, who took me so long to forget, remembered everything I had so long forgotten.

David Wagoner : Loons Mating 15

Their necks and their dark heads lifted into a dawn Blurred smooth by mist, the loons Beside each other are swimming slowly In charmed circles, their bodies stretched under water Through ripples quivering and sweeping apart The gray sky now held close by the lake's mercurial threshold Whose face and underface they share In wheeling and diving tandem, rising together To swell their breasts like swans, to go breasting forward With beaks turned down and in, near shore, Out of sight behind a windbreak of birch and alder, And now the haunted uprisen wailing call. And again, and now the beautiful sane laughter.

Lawrence Raab : The Sudden Appearance of a Monster at a Window 254

header note by milosz:

The frailty of so-called civilized life, our awareness that it lasts

merely by a miracle, because at any moment it could disintegrate and

reveal unmitigated horror, as has happened more than once in our century

- all this could contribute to the writing of this poem. Its author lives

in an idyllic New England, and has a window with a view of an orchard.

Yes, his face really is so terrible

you cannot turn away. And only

that thin sheet of glass between you,

clouding with his breath.

Behind him: the dark scribbles of trees

in the orchard, where you walked alone

just an hour ago, after the storm had passed,

watching water drip from the gnarled branches,

stepping carefully over the sodden fruit.

At any moment he could put his fist

right through that window. And on your side:

you could grab hold of this

letter opener, or even now try

very slowly to slide the revolver

out of the drawer of the desk in front of you.

But none of this will happen. And not because

you feel sorry for him, or detect

in his scarred face some helplessness

that shows in your own as compassion.

You will never know what he wanted,

what he might have done, since

this thing, of its own accord, turns away.

And because yours is a life in which

such a monster cannot figure for long,

you compose yourself, and return

to your letter about the storm, how it bent

the apple trees so low they dragged

on the ground, ruining the harvest.

William Carlos Williams: To a Poor Old Woman 191

munching a plum on the street a paper bag of them in her hand They taste good to her They taste good to her. They taste good to her You can see it by the way she gives herself to the one half sucked out in her hand Comforted a solace of ripe plums seeming to fill the air They taste good to her

Jelaluddin Rumi : Little by Little, Wean Yourself 271

Little by little, wean yourself. This is the gist of what I have to say. From an embryo, whose nourishment comes in the blood, move to an infant drinking milk, to a child on solid food, to a searcher after wisdom, to a hunter of more invisible game. Think how it is to have a conversation with an embryo. You might say, "The world outside is vast and intricate. There are wheatfields and mountain passes, and orchards in bloom. At night there are millions of galaxies, and in sunlight the beauty of friends dancing at a wedding." You ask the embryo why he, or she, stays cooped up in the dark with eyes closed. Listen to the answer. There is no "other world." I only know what I've experienced. You must be hallucinating. Mathnawi III 49-6

Jelaluddin Rumi : Out Beyond Ideas 276

[tr. Coleman Brooks and John Moyne] Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I'll meet you there. When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to talk about. Ideas, language, even the phrase each other doesn't make any sense

Miron Bialoszewski : A Ballad of Going Down to the Store 285

tr. from the Polish by Czeslaw Milosz from Milosz's headnote: Polish (Jew) poet, Miron Bialoszewski (1922-1983) survived and the complete destruction of Warsaw during WW2. A humourous poet, he describes the most ordinary human actions with an attention usually deserved by much greater events. First I went down to the store by means of the stairs, just imagine it, by means of the stairs. Then people known to people unknown passed by and I passed them by. Regret that you did not see how people walk, regret! I entered a complete store: lamps of glass were glowing. I saw somebody--he sat down-- and what did I hear? What did I hear? rustling of bags and human talk. And indeed, indeed, I returned.

Naomi Lazard : Ordinance on Arrival p.304

Welcome to you

who have managed to get here.

It's been a terrible trip;

you should be happy you have survived it.

Statistics prove that not many do.

You would like a bath, a hot meal,

a good night's sleep. Some of you

need medical attention.

None of this is available.

These things have always been

in short supply; now

they are impossible to obtain.

This is not

a temporary situation;

it is permanent.

Our condolences on your disappointment.

It is not our responsibility

everything you have heard about this place

is false. It is not our fault

you have been deceived,

ruined your health getting here.

For reasons beyond our control

there is no vehicle out.

Naomi Lazard is a very serious poet, and deserves to be

better known. Her work is very well regarded in India and

Pakistan thanks to her exceptional translations of Faiz;

read extensive excerpts from this work on Book Excerptise:

The true subject: selected poems of Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1988).

Zbigniew Herbert : Elegy of Fortinbras

To C. M. Now that we’re alone we can talk prince man to man though you lie on the stairs and see more than a dead ant nothing but black sun with broken rays I could never think of your hands without smiling and now that they lie on the stone like fallen nests they are as defenceless as before The end is exactly this The hands lie apart The sword lies apart The head apart and the knight's feet in soft slippers You will have a soldier's funeral without having been a soldier they only ritual I am acquainted with a little There will be no candles no singing only cannon-fuses and bursts crepe dragged on the pavement helmets boots artillery horses drums drums I know nothing exquisite those will be my manoeuvres before I start to rule one has to take the city by the neck and shake it a bit Anyhow you had to perish Hamlet you were not for life you believed in crystal notions not in human clay always twitching as if asleep you hunted chimeras wolfishly you crunched the air only to vomit you knew no human thing you did not know even how to breathe Now you have peace Hamlet you accomplished what you had to and you have peace The rest is not silence but belongs to me you chose the easier part an elegant thrust but what is heroic death compared with eternal watching with a cold apple in one's hand on a narrow chair with a view on the ant-ill and clock’ dial Adieu prince I have tasks a sewer project and a decree on prostitutes and beggars I must also elaborate a better system of prisons since as you justly said Denmark is a prison I go to my affairs This night is born a star named Hamlet We shall never meet what I shall leave will not be worth a tragedy It is not for us to greet each other or bid farewell we live on archipelagos and that water these words what can they do what can they do prince tr. Milosz & Scott link: Wilson Quarterly issue on Herbert, ed. Joseph Brodsky Modern poetry has a reputation for being difficult. It's hard to follow, harder still to scan, and there's almost no way to memorize it. The last job is so hard it gives you the impression that modern poetry doesn't want to be remembered, doesn't want to be poetry in the traditional sense. [...] Starkness, in fact, is very much Herbert's signature. also see: 20 poems

Index (by author)

the thematic organization used by Czeslaw makes it hard to trace the

individual poets. Here is an author-wise breakup of the poems.

Adam Zagajewski : Moths 19

Auto Mirror 128

Al Zolynas : Love in the Classroom 193

Zen of Housework 156

Aleksander Wat : A Joke 243

Facing Bonnard 70

From 'Songs of a Wanderer' 164

From Persian Parables 297

Aloysius Bertrand : The Mason 142

Anna Kamienska : A Prayer That Will Be Answered 290

Anna Swir : I Talk to My Body 233

I Starve My Belly for a Sublime Purpose 235

I'm afraid of fire 296

She Does Not Remember 220

Troubles with the Soul at Morning Calisthenics 234

I Wash the Shirt 204

Poetry Reading 259

Thank You, My Fate 222

The Same Inside 200

The Second Madrigal 223

The Greatest Love 219

The Sea and the Man 47

Antonio Machado : Rainbow at Night 93

Summer Night 132

Blaise Cendrars : Fish Cove 80

Aleutian Islands 79

Frisco-City 83

Harvest 81

South 82

Bronislaw Maj : A Leaf 258

An August Afternoon 158

Seen Fleetingly, from a Train 97

Carlos Drummond de Andrade : In the Middle of the Road 8

Ch'ang Yu : A Ringing Bell 279

Ch'in Juan : Along the Grand Canal 100

Chang Chi : Coming at Night to a Fisherman's Hut 85

Chang Yan-hao : Recalling the Past at T'ung Pass 91

Charles Simic : Empire of Dreams 171

Chu Shu Chen : Morning 216

Chuang Tzu : Man Is Born in Tao 274

The Need to Win 275

Constantine Cavafy : Supplication 184

Waiting for the Barbarians 305

D.H. Lawrence : Butterfly 31

Maximus 5

Mystic 36

David Kirby : To a French Structuralist 131

David Wagoner : Loons Mating 15

The Author of American Ornithology Sketches a Bird, Now Extinct 13

Denise Levertov : Living 24

A Woman Meets an Old Lover 228

Eye Mask 266

Living 24

Witness 72

Eamon Grennan : Woman at Lit Window 169

Edward Field : A Journey 98

Elizabeth Bishop : Brazil, January 1, 1502 121

Emily Dickinson : A Narrow Fellow in the Grass 45

Emperor Ch'ien-wen of Liang : Getting up in Winter 226

Eskimo (anonymous) : Magic Words 268

Francis Ponge : The Frog 69

Franz Wright : Depiction of Childhood 250

Galway Kinnell : Daybreak 35

Gary Snyder : Dragonfly 32

Late October Camping in the Sawtooths 151

Gunnar Ekëlof : Greece 125

Issa : Haiku 6

From the bough

floating down river

insect song

Kikaku : Haiku 6

Above the boat

bellies

of wild geese

tr. Lucien Stryk and Takashi Ikemoto (both haikus)

Jaan Kaplinski : We Started Home, my Son and I 103

My Wife and Children 167

James Applewhite : Prayer for My Son 119

James Tate : Teaching the Ape to Write 251

Jane Hirshfield : A Story 42

Jean Follain : A Mirror 225

A Taxidermist 16

Black Meat 161

Buying 160

Face the Animal 43

Music of Spheres 7

School and Nature 162

Jelaluddin Rumi : Little by Little, Wean Yourself 271

Out Beyond Ideas 276

Joanne Kyger : And with March a Decade in Bolinas 242

Destruction 38

John Haines : On the Mountain 102

Jorge Guillén : Flight 44

Joseph Brodsky : In the Lake District 115

Odysseus to Telemachus 116

Judah Al-Harizi : The Lightning 58

Judah Al-Harizi : The Lute 59

Judah Al-Harizi : The Sun 58

Julia Hartwig : Above Us 298

Keith Wilson : Dusk in My Backyard 152

Kenneth Rexroth : From 'The City of the Moon' 287

Kenneth Rexroth : Signature of All Things 144

Kenneth Rexroth : The Heart of Herakles 146

Kikaku : Haiku 6

Lawrence Raab : The Sudden Appearance of a Monster at a Window

254

Leonard Nathan : Bladder Song 197

Leonard Nathan : Toast 196

Leopold Staff : Foundations 295

Li Ch'ing-chao : Hopelessness 218

Li Po : Ancient Air 84

Li Po : Ancient Air 88

Li Po : The Birds Have Vanished 277

Li-Young Lee : Irises 17

Linda Gregg : A Dark Thing Inside the Day 163

Linda Gregg : Adult 221

Linda Gregg : Night Music 127

Liu Tsung-Yüan : Old Fisherman 135

Louis Simpson : After Midnight 117

Mary Oliver : The Kingfisher 20

Wild Geese 40

May Swenson : Question 229

Mei Yao Ch'en : A Dream at Nght 182

Miron Bialoszewski : A Ballad of Going Down to the Store 285

Moushegh Ishkhan : The Armenian Language is the Home of the Armenian 303

Muso Soseki : Magnificent Peak 71

Muso Soseki : Old Man at Leisure 286

Nachman of Bratzlav : From 'The Torah of the Void' 269

Naomi Lazard : Ordinance on Arrival 304

Oscar V. de L. Milosz : The Bridge 166

Ou Yang Hsiu : Fisherman 134

Philip Larkin : The Card-Players 201

Philip Levine : A Sleepless Night 26

Po Chü-I : Sleeping on Horseback 172

A Dream of Mountaineering 87

After Collecting the Autumn Taxes 111

After Getting Drunk, Becoming Sober in the Night 246

Climbing the Ling-Ying Terrance and Looking North 267

Golden Bells 245

Lodging with the Old Man of the Stream 284

Rain 112

Starting Early 86

The Philosophers: Lao-tzu 244

Madly Singing in the Mountains 120

Rainer Maria Rilke : Going Blind 195

Raymond Carver : The Window 159

Raymond Caver : Wine 248

Robert Creeley : Like They Say 18

Robert Francis : Waxwings 25

Robert Frost : The Most of It 46

Robert Hass : Late Spring 27

The Image 62

Robert Morgan : Bellrope 57

Honey 37

Robinson Jeffers : Boats in Fog 60

Carmel Point 34

Cremation 230

Evening Ebb 61

Rolf Jacobsen : Cobalt 63

Express Train 92

Rubber 155

The Catacombs in San Callisto 124

Ryszard Krynicki : I Can't Help You 300

Sandor Weores : Rain 174

The Plain 129

Seamus Heaney : From 'Clearances', In Memoriam M.K.H. (1911-1984) 183

Sharon Olds : I Go Back to May 1937 205

Shu Ting : Perhaps... 299

Southern Bushmen : The Day We Die 289

Steve Kowit : In the Morning 215

Cosmetics Do No Good 217

Notice 199

What Chord Did She Pluck 227

When He Pressed His Lips 224

Su Man Shu : Exile in Japan 114

Su Tung P'o : On a Painting by Wang the Clerk of Yen Ling 56

Tadeusz Rozewicz : A Sketch for a Modern Love Poem 231

Tadeusz Rozewicz : A Voice 207

Ted Kooser : Late Lights in Minnesota 153

Theodore Roethke : Carnations 33

Moss-Gathering 23

Thomas Merton : An Elegy for Ernest Hemingway 208

Tomas Tranströmer : Outskirts 130

Syros 126

Tracks 154

Tu Fu : Another Spring 113

Clean After Rain 150

Dejeuner sur l'Herbe 241

Coming Home Late at Night 256

Snow Storm 257

South Wind 149

Sunset 147

To Pi Ssu Yao 181

Traveling Northward 110

Visitors 283

Winter Dawn 148

Valery Larbaud : Images 77

W.S. Merwin : Dusk in Winter 30

For the Anniversary of My Death 272

Utterance 198

Wallace Stevens : Study of Two Pears 64

Walt Whitman : A Farmer Picture 55

A Noiseless Patient Spider 210

A Sight in Camp in the Daybreak Gray and Dim 187

As Toilsome I Wander'd Virginia's Woods 186

By the Bivoac's Fitful Flame 168

Cavalry Crossing a Ford 141

From 'I Sing the Body Electric' 185

Dirge for Two Veterans 188

From 'The Sleepers' 202

I Am the Poet 53

The Runner 55

Wang Chien : The New Wife 192

The South 109

Wang Wei : Dancing Woman, Cockfighter Husband, and the Impoverished Sage 180

A Farewell 281

A White Turtle Under a Waterfall 133

Drifting on the Lake 282

Lazy about Writing Poems 280

Magnolia Basin 136

Morning, Sailing into Xinyang 101

Song about Xi Shi 179

Song of Marching with the Army 89

Watching the Hunt 90

Wayne Dodd : Of Rain and Air 173

William Blake : From 'Milton' 54

William Carlos Williams : To a Poor Old Woman 191

Proletarian Portrait 190

The Red Wheelbarrow 66

William Stafford : Vacation 95

Wislawa Szymborska : Four in the Morning 22

In Praise of My Sister 252

In Praise of Self-Deprecation 21

Seen from Above 41

View with a Grain of Sand 67

Yoruba Tribe : Invocation of the Creator 273

Zbigniew Herbert : Elegy of Fortinbras 301

Zbigniew Machej : Orchards in July 29

--- blurb:

Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz selects and introduces 300 of his favorite

poems in this "magnificent collection" that ranges "widely across time and

continents, from eighth century China to contemporary americana" (San

Francisco Chronicle).

bookexcerptise is maintained by a small group of editors. get in touch with us! bookexcerptise [at] gmail [dot] .com. This review by Amit Mukerjee was last updated on : 2015 Aug 26