Emergence: contemporary readings in philosophy and science

Mark Bedau and Paul Humphreys (eds)

Bedau, Mark; Paul Humphreys (eds);

Emergence: contemporary readings in philosophy and science

MIT Press Bradford Books, 2008, 464 pages

ISBN 0262524759, 9780262524759

topics: | philosophy | science | emergence

Dennett: Real Patterns 189

Are there really beliefs? Or are we learning (from neuroscience and

psychology, presumably) that, strictly speaking, beliefs are figments of our

imagination, items in a superseded ontology?

Are centers of gravity in your ontology?

[argument / thought expt from "Intentional Stance"]

philosophers feel when it comes to beliefs (and other mental items) one

must be either a realist or an eliminative materialist.

... my analogizing beliefs to centers of gravity has been attacked from both

sides of the ontological dichotomy, by philosophers who think it is simply

obvious that centers of gravity are useful fictions, and by philosophers who

think it is simply obvious that centers of gravity are perfectly real:

The trouble with these supposed parallels . . . is that they are all

strictly speaking false, although they are no doubt useful

simplifications for many purposes. It is false, for example, that the

gravitational attraction between the Earth and the Moon involves two

point masses; but it is a good enough first approximation for many

calculations. However, this is not at all what Dennett really wants to

say about intentional states. For he insists that to adopt the

intentional stance and interpret an agent as acting on certain beliefs

and desires is to discern a pattern in his actions which is genuinely

there (a pattern which is missed if we instead adopt a scientific

stance): Dennett certainly does not hold that the role of intentional

ascriptions is merely to give us a useful approximation to a truth that

can be more accurately expressed in non-intentional terms.3

Compare this with Fred Dretske’s4 equally confident assertion of realism:

I am a realist about centers of gravity. . . . The earth obviously exerts

a gravitational attraction on all parts of the moon—not just its center

of gravity. The resultant force, a vector sum, acts through a point, but

this is something quite different. One should be very clear about what

centers of gravity are before deciding whether to be literal about them,

before deciding whether or not to be a center-of-gravity realist. (ibid.,

p. 511)

trivial abstract object: Dennett’s lost sock center: the point defined as the

center of the smallest sphere that can be inscribed around all the socks I

have ever lost in my life.

[has] the same metaphysical status as centers of gravity.

centers of gravity are real because they are (somehow) good abstract objects.

I have claimed that beliefs are best considered to be abstract objects rather

like centers of gravity.

Dennett's position: a mild and intermediate sort of realism is a positively

attractive position,

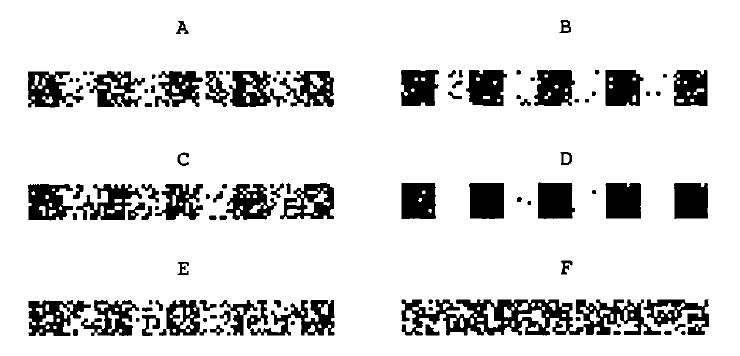

patterns A to F. Are they different or same?

Dennett reveals that pattern A to F were Generated by having a program write

ten lines, each w ten dots then ten blanks, with noise: A to F: 25% 10% 25%

1% 33% 50%.

Chaitin's definition of randomness as incompressibility.

How many bits do we need to transmit the image?

a. all 900 bits - needed for F

b. "ten square patterns", except for dots at 55, 73, etc. - may be smaller

for patterns with greater "regularity" - B, D etc.

Any shorter description is a description of a real pattern in the data.

patterns A to F. Are they different or same?

Dennett reveals that pattern A to F were Generated by having a program write

ten lines, each w ten dots then ten blanks, with noise: A to F: 25% 10% 25%

1% 33% 50%.

Chaitin's definition of randomness as incompressibility.

How many bits do we need to transmit the image?

a. all 900 bits - needed for F

b. "ten square patterns", except for dots at 55, 73, etc. - may be smaller

for patterns with greater "regularity" - B, D etc.

Any shorter description is a description of a real pattern in the data.

Contents

Preface ix

Acknowledgments xi

Sources xiii

Introduction 1

I Philosophical Perspectives on Emergence 7

Introduction to Philosophical Perspectives on Emergence

1 The Rise and Fall of British Emergentism 19

Brian P. McLaughlin

2 On the Idea of Emergence 61

Carl Hempel and Paul Oppenheim

3 Reductionism and the Irreducibility of Consciousness 69

John Searle

4 Emergence and Supervenience 81

Brian P. McLaughlin

5 Aggregativity: Reductive Heuristics for Finding Emergence 99

William C. Wimsatt

6 How Properties Emerge 111

Paul Humphreys

7 Making Sense of Emergence 127

Jaegwon Kim

8 Downward Causation and Autonomy in Weak Emergence 155

Mark A. Bedau

9 Real Patterns 189

Daniel C. Dennett

II Scientific Perspectives on Emergence 207

Introduction to Scientific Perspectives on Emergence

10 More Is Different: Broken Symmetry and the Nature of the Hierarchical Structure

of Science 221

P. W. Anderson

11 Emergence 231

Andrew Assad and Norman H. Packard

12 Sorting and Mixing: Race and Sex 235

Thomas Schelling

13 Alternative Views of Complexity 249

Herbert Simon

14 The Theory of Everything 259

Robert B. Laughlin and David Pines

15 Is Anything Ever New? Considering Emergence 269

James P. Crutchfield

16 Design, Observation, Surprise! A Test of Emergence 287

Edmund M. A. Ronald, Moshe Sipper, and Mathieu S. Capcarre`re

17 Ansatz for Dynamical Hierarchies 305

Steen Rasmussen, Nils A. Baas, Bernd Mayer, and Martin Nillson

III Background and Polemics 335

Introduction to Background and Polemics

18 Newtonianism, Reductionism, and the Art of Congressional Testimony 345

Stephen Weinberg

19 Issues in the Logic of Reductive Explanations 359

Ernest Nagel

20 Chaos 375

James P. Crutchfield, J. Doyne Farmer, Norman H. Packard, and Robert S. Shaw

21 Undecidability and Intractability in Theoretical Physics 387

Stephen Wolfram

22 Special Sciences (Or: The Disunity of Science as a Working Hypothesis) 395

Jerry Fodor

23 Supervenience 411

David Chalmers

24 The Nonreductivist’s Troubles with Mental Causation 427

Jaegwon Kim

amitabha mukerjee (mukerjee [at-symbol] gmail) 2012 Feb 12